As the end of Latin Heritage Month (September 15 to October 15) overlapped with the High Holy Days this year, I was left reflecting on the nature of my intersecting identities as Brazilian and Jewish. I was reminded of Misha Klein's Kosher Feijoada and Other Paradoxes of Jewish Life in São Paulo, which provides an anthropological study of Brazilian Jewish communities and their navigation of identity, resilience, and culture.

Through the example of feijoada, a traditional Brazilian black bean stew cooked with beef and pork, Klein explores how communities can simultaneously hold their Jewish traditions while developing an identity in relation to the land in which they find themselves. The creation of kosher feijoada highlights a commitment to keeping kashrut, while simultaneously not allowing a dietary restriction to become a barrier from engaging with their national culture. One may tease that feijoada made without pork would lack a certain flavor or authenticity, but it also highlights a beautiful example of cultural tension becoming a catalyst for reinvention.

It was in the "paradox" of holding both Brazilian and Jewish traditions that a new dish was born, and a new form of expression was established. As opposed to seeing intersecting identities as conflicting, we can reframe this dynamic to instead focus on what can emerge from only the combination of their parts. We are not made up of halves of our ancestors; rather, we fully embody each of our identities, and it is in the totality of who we are that new forms of manifestation and realization arise.

For me, this emerges in how I understand migration, belonging, and the pursuit of home. It is within my existence as the great-granddaughter of ancestors murdered in the Holocaust and my descendance from the Brazilian Guarani tribe that I find a voice and passion for migration justice.

As the daughter of immigrants who followed two distinct paths to United States, I am informed by each of their journeys in the pursuit of a better future. As often as Latin and Jewish identities are proposed as juxtaposing notions, there is clear synergy in the lessons that the communities share, their embedded values, and the historical and present struggle for belonging and home. I find strong cultural parallels in the warm hospitality of both communities I grew up within, characterized by generously ambiguous understandings of family, grandmothers with a passion for feeding, and front doors left ajar for holidays. I am guided by the voices and stories of all my ancestors in this holy work, as their words inspire resilience and pride. In the context of my family's history of migration, I have come to understand home as defined by who is there as opposed to the land it is on. Belonging, I have found, is not a given for many migrants and minority populations, but rather an active and continuous pursuit for acceptance. Sometimes our search for belonging is itself an act of defiance as we normalize our presence.

As Jews, we just finished celebrating Sukkot, a holiday which centers around the creation of a makeshift home, a reminder of the forty years in which the Israelites wandered after their liberation from Egypt. By giving up our houses temporarily to eat, sleep, and spend time in the sukkah, we are reminded of the need for a home and its fragile nature. Yet, we simultaneously complicate the notion of home, as we create a sense of community and joy in the sukkah, disrupting the assumption that home can only be found in the confines of a house.

The sukkah reminds us that despite migration and displacement, an abode can be created by components far simpler than the physical structure of a modern building. Jewish tradition teaches us to hold our memory of being a stranger in the land of Egypt as a reminder to welcome others into the fold, especially those in need. Our teachings are strong in their call to protect and love the stranger, and Sukkot reminds us that the establishment of home is not a given or immediate process. And yet, these values, teachings, and traditions are only as meaningful as our ability to apply them to the modern context around us.

Nowhere is the pursuit of home more alive than in the work of the Home is Here coalition fighting for the protection of DACA recipients. Their bold declaration of belonging exemplifies an unapologetic reclamation of home, as they refuse to be silenced or have their stories told for them. As Sukkot reminds us of the experience of living in tumultuous times without a grounded home, solidarity with my Latinx siblings has connected me to the modern-day fight for acceptance and recognition of belonging. This fight for the protection of DACA recipients emphasizes the modern struggle that our Jewish values teach us to speak up on. A similar struggle is also highlighted by United We Dream and other immigration organizations who have placed billboards across major states proclaiming, "Immigrants Are Welcome Here." These signs echo a call for acceptance and belonging that is all too familiar for Jews in our fight for belonging as a minority group in the face of antisemitism.

It is in the combination of my two identities and the wisdom of all the ancestors that came before me that I have come to more fully understand the universal pursuit of home. A richer and more inclusive Judaism requires a shift in mindset from viewing intersectionality as competing identities, and rather creating space for what can be built in its unison. It is in reaching across "conflicting identities" that we find wisdom that can enrich our culture, community, and coalitions to best address the most challenging issues today. In expanding our understandings of Jewish expression, we can better show up in the pursuit of justice.

Related Posts

RAC-NY Update

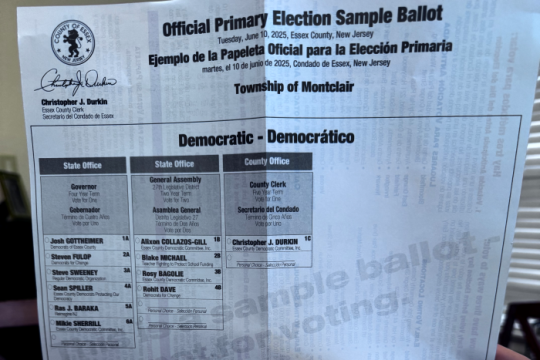

Lessons from the 2025 NJ Primary Election