Parashat Yitro and Judicial Discretion

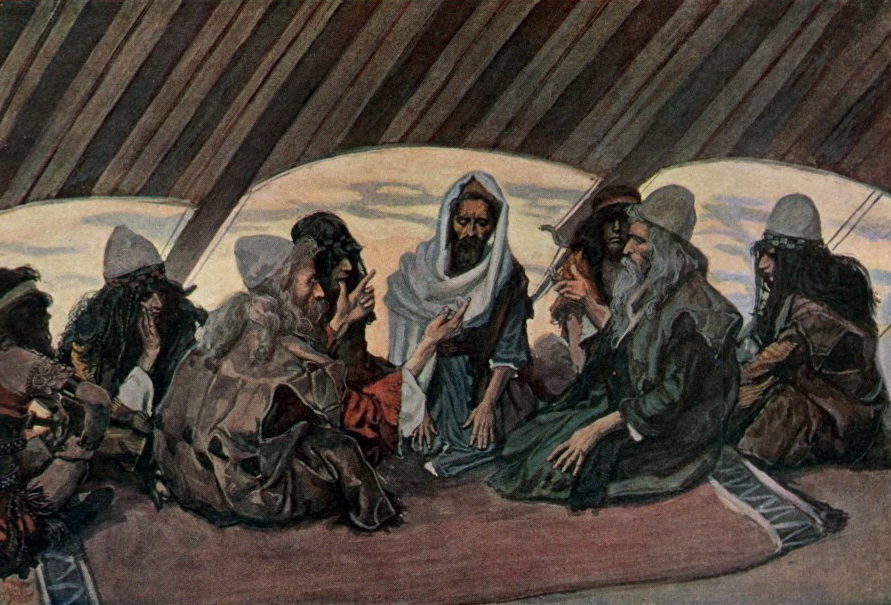

This week’s parshah is Yitro (Jethro), from the Book of Exodus. The parshah opens as Moses, who has brought the Israelites out of Egypt, is visited by his father-in-law, Jethro. Jethro witnesses that Moses has assumed the role of sole arbiter over the Israelites and scolds his son-in-law, saying that such a practice will wear Moses out and reminding him that “you cannot do it alone” (Exodus 18:18). As an alternative, Jethro advises Moses to “choose out of the entire nation men of substance, God fearers, men of truth, who hate monetary gain” to act as judges in the day-to-day legal affairs of the people (18:21). More serious concerns are still to be reserved for Moses’ judgment, as he can seek God’s assistance in rendering a decision, but minor concerns are to fall under the purview of the appointed judges. In this way, a tiered judicial system is created among the Israelites to ensure that justice is granted in all cases.

We can think about Jethro’s advice to Moses in the context of the contemporary U.S. criminal justice system. Our system operates in tension with a foundational legal and judicial principle of the Jewish tradition: judicial discretion.

Federal sentencing laws have prevented judges from carrying out the necessary function of determining crime and punishment, especially regarding drug offenses. Nearly half of the more than 200,000 prisoners in federal facilities are serving time for drug offenses. Although many of these individuals committed nonviolent offenses, they have been sentenced to decades in prison because federal legal statutes established over the past three decades require a harsh mandatory minimum sentence. Judges themselves have decried being legally bound to administer punishments that they deem wholly unfair and incompatible with the severity of the crime.

It was exactly because Moses was unable to fully dedicate himself to careful study and consideration of each and every case that Jethro recommended appointing a system of judges to assist him. Rather than embracing the importance of individualized judgment, however, we have chosen to create a system of blanket punishments that disregard the larger context in which a crime was committed.

Fortunately, pending legislation at the federal level would begin to address judicial discretion in setting sentences for nonviolent drug offenders. The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act (S. 2123) and the Sentencing Reform Act (H.R. 3713) both include provisions to expand existing provisions in the legal code and to create new provisions whereby judges can choose to circumvent administering the mandatory minimum sentence if the offender’s prior criminal history is limited. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, several thousand offenders each year could see their sentences reduced by an average of 20 percent as a result of these measures.

As beneficial as the impacts of S. 2123 and H.R. 3713 would be, there is still more work to be done. Mandatory minimums, while significantly reduced, are left intact, and S. 2123 actually creates new mandatory minimums for certain offenses. This means that, in thousands of cases each year, judges will still be required to give a harsh punishment, regardless of whether or not they believe that punishment to be just. The lessons and principles communicated to us in Yitro remind us of the importance of a criminal justice system that reflects good and fair judgment.

Related Posts

Inside the Inaugural L'Taken Canada

Five Definitions of Antisemitism