The original article appeared in Robert P. Jones's "White Too Long" newsletter.

On July 5, 1852, the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester invited Frederick Douglass to give a speech on the 76th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, which became known by its central piercing question, "What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?" Never one to sugarcoat his message, Douglass handed the good-willed ladies of Rochester a stinging indictment of the hypocrisy in white American celebrations of independence:

"I am not included within the pale of [your] glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity, and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me…. This Fourth July is yours, not mine."

But Douglass also held out hope that the United States might yet live to be a nation worthy of its professed values. "Notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation," he declared, "I do not despair of this country."

More than a century later, in the South of my childhood, the contradictions between the principles of equality enumerated in the Declaration of Independence and the glaring racial inequities permeating our community remained hidden in our Fourth of July celebrations. To our whites-only Southern Baptist congregation, the Fourth of July was our holiday, proudly celebrating our rightful inheritance of the American promised land. But what, to the white American, is the 19th of June?

Unlike most white Americans, I grew up with a vague awareness of Juneteenth due to two coincidental factors. First, June 19th is my birthday; and second, I spent my preschool years in Texas, where the holiday was most prominently in the public eye. But I was also told that this was a holiday Black people celebrated. Juneteenth was their holiday. It had nothing to do with us.

But, of course, Juneteenth has everything to do with us. And on June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden made it official, signing legislation making June 19th a national holiday for all Americans.

In a recent conversation, my good friend Rev. Jacqui Lewis, the innovative senior minister of Middle Collegiate Church in New York City, suggested that because of its proximity to Independence Day, both temporally and conceptually, our newest federal holiday has powerful potential to help rehabilitate the 4th of July from the jingoistic Christian nationalism it all too often evokes. I've been thinking about that insight a lot over the past few days.

Among the many gifts of being in an interfaith marriage is the ongoing invitation to experience and learn from a tradition that is not your own. As I've participated in the Jewish High Holidays over the last 20 years, I've been moved by the power of the moral space that opens in the ten days between a celebration of the promise of the new year on Rosh Hashanah and lament over the failings of the past at Yom Kippur. The sweetness of apples, honey, and kugel foreshadows repentance, fasting, and atonement. Like binary stars, these holidays orbit one another, generating a contemplative space between them known as the "days of awe."

The period of 15 days that span the space between Juneteenth and Independence Day could similarly function as an enduring season of critical patriotism for our time. Alongside the celebratory fireworks and other well-established practices surrounding the 4th of July, we could develop new rituals that include the creative interplay of lament and celebration, reckoning and repair, truth-telling and re-envisioning.

Borrowing from the High Holidays model, we could conceptualize this season from Juneteenth to the Fourth of July as the "days of freedom and equality." We could also embrace a conviction that is deeply engrained in Judaism, Christianity, and indeed most religious traditions-that no people can live with integrity into the future if they cannot face failures to live up to their principles in the past.

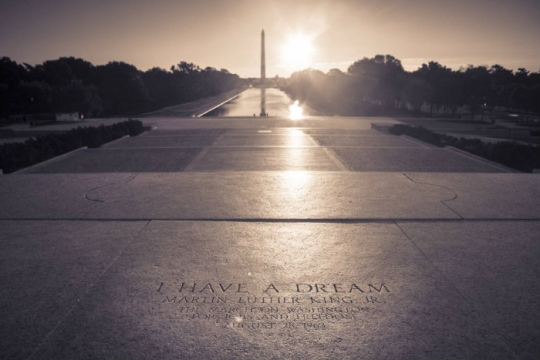

Conceptualizing the 19th of June and the 4th of July together, in a creative mutual orbit where each is held by the gravitational force of the other, can help us develop rituals and stories that are honest about our country's failings while also being hopeful about its possibilities. Beginning this season with Juneteenth can help us-especially white Americans-recalibrate Independence Day, as Douglass admonished his fellow Americans to do, as an opportunity to conduct a more forthright assessment of America as a work in progress. Such a season of critical patriotism would be one all of us could embrace.

Related Posts