This is an excerpt from a sermon delivered on July 15, 2016. Read the full sermon here.

A few weeks ago, in Parashat Chukat, we find the Israelites in the desert doing what they do best — complaining. This time, they don't have water. So they bring their grievance to Moses. “Why did you bring us out into this desert to die! We wish we'd never left Egypt!”

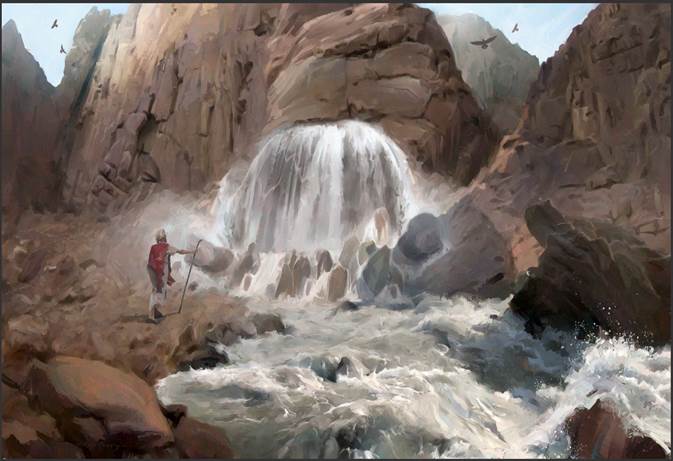

One can maybe forgive, or at least understand, Moses’s overreaction. He's fed up. So in anger he strikes the rock to make the water flow. The problem was, God had told him just to take his staff and assemble the people at the rock — not to hit it. Moses uses excessive force, and God sanctions him harshly — no Promised Land for him. It seems unfair, for such a misstep. But then again, do we not hold leaders to a higher standard?

This episode jumped off the page for me this week, though it's going to take me a moment to explain why. Our country is reeling from violence by and against police, by racial tensions boiling over, by the deliberate and vicious murder of five Dallas police officers — Brent Thompson, Patrick Zamarripa, Michael Krol, Michael Smith, and Lorne Ahrens — who were doing their jobs by keeping watch at what started as a peaceful protest against police bias and the killing of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile.

We ask the police to do too many jobs, and then we’re surprised when things go wrong. In addition to public safety, for which they put their lives on the line every day, we ask them to be social workers, mental health professionals, drug treatment specialists, social safety nets for homelessness and poverty.

Why? Because we have failed to live up to our responsibilities as citizens. We have failed to create communities that take care of— to put it in biblical terms — the widow and the orphan. We have failed to invest in infrastructure, mental health, drug treatment; we have failed to make the promise of a good education available to every child, and the promise of a good job to everyone willing to work for it. What kind of society criminalizes addiction, homelessness, depression — instead of treating and caring for them?

The Israelites look at the challenges they face in the desert as free people, and they whine—freedom, they're starting to learn, means responsibility. They could have said: Hey, there's a water shortage, let's work together to fix it so no one goes thirsty. But what do they do? They air their grievance and demand that their leader just fix it already! There is a shockingly fine line between enslavement and entitlement.

Is that what we've become? People who prefer the chains of Egypt to the challenge of the wilderness? Experts in outrage instead of initiative? Complaint instead of compromise?

What we can do instead is stop whining, and start working. Step out of our political echo chambers and say to those across the divide: We've got real problems here, and we all have a stake in this. You have some of the answers, and we have some of the answers, and we need each other. We are not enemies but partners.

I hope, if nothing else, that you will pause every now and then and think of the complaining Israelites. When you find yourself tempted to say, “If only black people would…" Or, “If only the police would…" Or, “If only the President and Congress would…" — just wait. I learned recently that “WAIT” is an acronym for "Why Am I Talking?" Ask yourself: Am I trafficking in outrage? Am I whining about how it’s someone else's problem? Am I pretending like I don't bear any responsibility?

Don't get me wrong. We need to have uncomfortable conversations about #BlackLivesMatter and racial bias in the criminal justice system, about supporting the police and pushing for systemic reform, about broken families and broken communities. But it doesn't work if you enter the conversation as a whiner, a complainer, with an it's-not-my-problem, finger-pointing, blame-laying pretense of deniability.

Last century, during another generation’s civil rights struggle, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said, “In a free society, some are guilty, but all are responsible.” Moses was guilty of using excessive force, and he suffered the consequences. But we are all responsible for creating the conditions that enabled that act of violence, that shattering of the rock. Today, we are all responsible for picking up the pieces and fixing it.

Rabbi David Segal is the spiritual leader of the Aspen Jewish Congregation, in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. He is a graduate of Hebrew Union College (NYC) and the Wexner Graduate Fellowship.

Related Posts

Remarks from Rabbi Eliana Fischel at Jewish Gathering for Abortion Access

Teens from North Carolina Speak About Environmental Justice